Lesson #02 - You Are Never Ready

I sense the question is coming before it’s asked. A slightly raised eyebrow, the hint of a smile, almost accusatory as though I am trying to put one over them.

“Were you ready?” they ask.

You’d think I’d have a ready answer to a question asked so often. One I’d prepared earlier.

Maybe it is less question and more response when people learn I was appointed CEO of the Richmond Football Club at age 24.

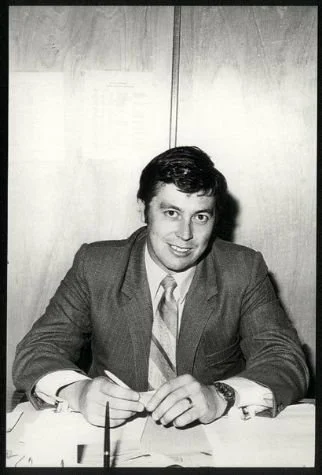

I look at the image from the press conference when my appointment was announced. I look more like a member of a boy band than a CEO, or General Manager as the position was then known, of a professional football club. I do remember a Gordon Gekko ‘Wall Street’ vibe in my choice of suit. “Lunch is for wimps” is the line I remember. It is a futile attempt to add some years and certitude. “Fake it to you make it” is the adage that comes to mind, a concept as vapid then as now.

I have never really had a good answer, but as years pass, I now understand when taking on anything difficult, be it a personal goal, ambition or desire, or a circumstance or situation you find yourself, my answer is now:

“You are never ready”.

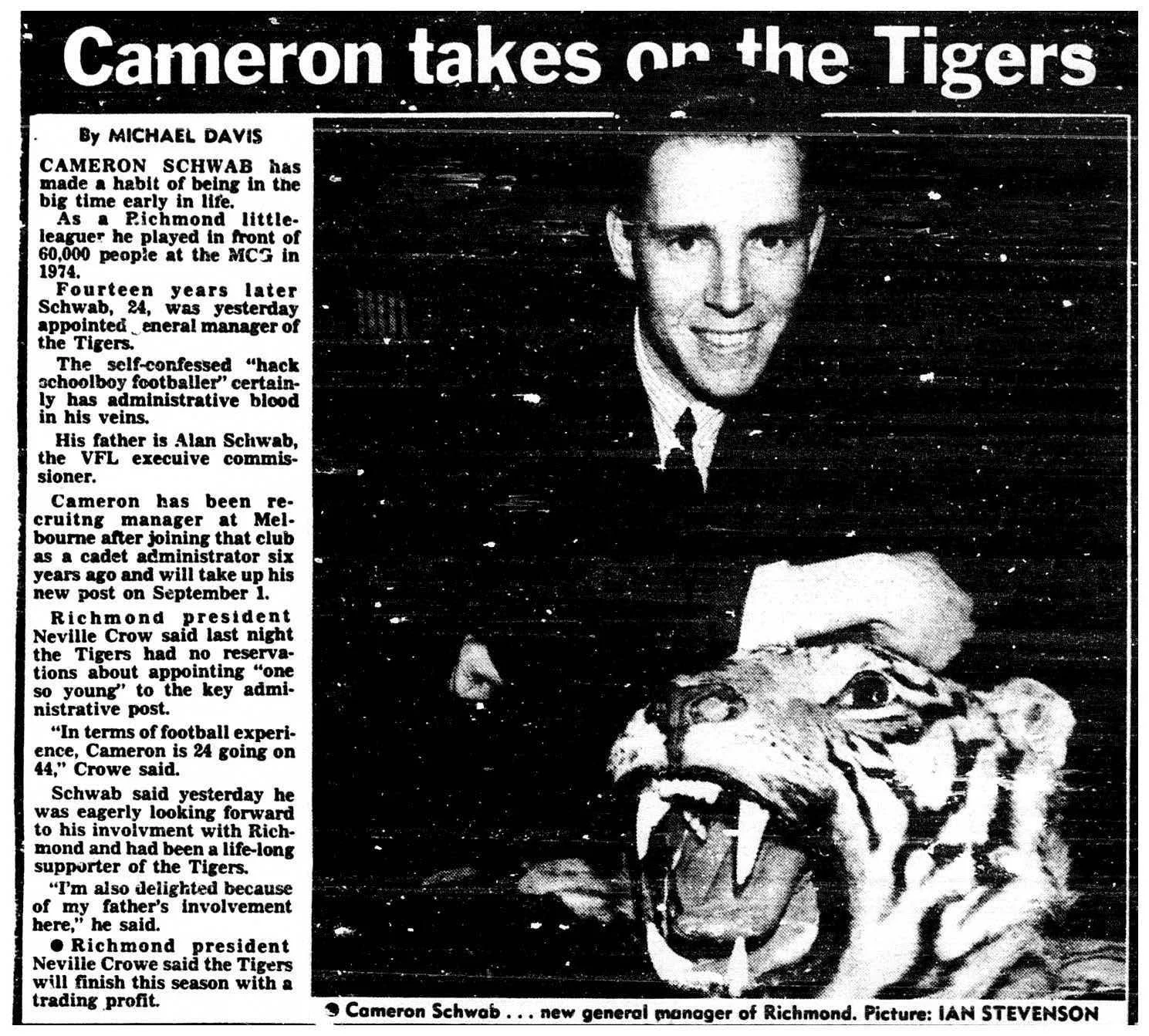

Alan Schwab, my father, as the young Richmond football Club Secretary

At the time, Richmond was in a mess. Millions in debt, last on the ladder. The club had been in free fall since their recent success era, which netted five Premierships, the last only eight years earlier winning the 1980 Grand Final, trouncing the old foe Collingwood by a then-record margin. I watched the game from the stands as an elated sixteen-year-old Richmond fanatic.

It was an era of success that paled all of the club’s historic achievements. It would become the marker for which all future teams and efforts would be compared and calibrated, adding layers of expectation on those who now had their hands on the levers.

It was also a period in which the club built a reputation of letting nothing get in the way of its success. The club was known as Ruthless Richmond, and I had more than a front-row seat with my father Alan Schwab being the CEO, although in those days, the position was known as Secretary. Title inflation, but in some ways more representative of the role. It is, after all, a football club. “Too much of a business to be a sport, and too much of a sport to be a business”, the famous 1920s baseball quote goes.

I like to say I fell in love with the game before I fell in love with anything else, but more specifically, it was the Richmond Football Club. The Tigers.

People would say it’s in my blood, but that is too obvious. I felt it in my nervous system, not just my bloodstream, the way the whole body responds when you bungee jump or stub your toe on a piece of furniture. All of me felt the game, club and team.

Growing up, it seemed there was our life, whilst others lived something less interesting, not as meaningful.

But as well as being colourful, it was complex and messy.

So many layers. The folklore. Where it had come from, romantic stories of victories and losses, the heroes, some unlikely, others predestined. The past always present. The aesthetic and mindset. The best of breed athleticism and potential for acts of sublime sporting prowess.

But it was also ugly, awful and lousy. Often heartbreaking with an inherent capacity for catastrophe, yet so alive in the moment. The immediacy and judgement. Its volatility and capacity for conflict, and almost overwhelmingly, its anxiety. The promise and fear of what comes next, giving all of the impression that you can control what you simply cannot.

As a lad growing up, my experiences with the game and club broadened me in ways that perhaps it should not have. The best and worst of male behaviour, including my father, who was my hero. But it also narrowed me such that I somehow sensed the experience would be the basis by which I judged the potential of any other effort or ambition.

I didn’t just want to fit into this world. I felt a deep need to belong in ways that I did not and could not understand as a boy. To be part of its rituals and test myself in all of its unknown provocations, risks, and possibilities. Like you would when standing on the edge of the platform on the high-board at the Ashburton Swimming Pool, or pushing off on your chalky wheeled skateboard when testing yourself one hill at a time, increasing gradient, velocity and capacity to inflict hurt with each Mt Waverley hill.

I was now aware that the game was not merely background. It dictated the rhythm of our household, its energy and attention, self-esteem, and identity.

So, was I ready?

When approached to consider the role, with a full understanding of the state of the club both on and off the field, I remember speaking to my father, who was now Executive Commissioner of the AFL, and I said:

“Dad, I don’t think it is a very good job”.

He paused, and with a smile I still miss every day, he responded:

“If it was a very good job Cam, they would not be asking you”.

I understood what he meant. There was not an ounce of negativity or judgement. It was the opposite. I felt his confidence in me. That it wasn’t a good job was the reason for the opportunity and why he thought I was the right person.

As someone appointed to, and removed from CEO roles, I have learned that you know the least about the considerations and conversations that lead to your enlistment or dismissal, and it is mostly out of your control. You have been the subject of discussions by dozens of others before the role is offered, or your career terminated.

When I was offered the position at Richmond, I was Recruiting Manager of the Melbourne Football Club. After decades in the wilderness, Melbourne was beginning to enjoy some success, playing off, but being thrashed, by a formidable Hawthorn in that year’s Grand Final. Melbourne’s ascension meant the reputations of individuals rose on its tide, including mine. I was now being ‘talked-up’ as someone who would play a more prominent role in the game, amplified by my ‘bloodlines’. My father had been a leader in the game for 20 years, his brother Frank umpired a Grand Final, and Frank’s son and my cousin Peter had played in that same Hawthorn premiership team.

I started to see career possibilities in the game, daring to dream. Maybe someday, I will get to be a club CEO. Then I was presented with that very prospect at the club that had been my obsession.

I accepted the role.

I had only worked six years in my entire life and had no formal education beyond a modest year 12, which included no business subjects. I had, however, been a self-anointed Student of the Game of Australian Football for a large part of my life.

As a young lad, I was watching the iconic World of Sport one Sunday, and Kevin Sheedy, the champion Richmond player, was competing in the Handball Championship, a weekly segment on the show. Having won comprehensively, he was asked to explain his handball technique, different to all other players of his generation. It was his invention, and he’d even given it a name, the Rocket. The ball spun backwards from the fist with more speed and accuracy. With handball becoming an offensive weapon in the ever-evolving possession game, all players would soon utilise this technique. Fifty years on, it is the method taught to kids in AusKick programs across the country.

During this segment, Sheedy was described as a Student of the Game, and even at the height of his playing days, he was talked of as a future coach. A year after his retirement as a player, at the age of 32, he was appointed coach of Essendon, a role he held for the next twenty-seven years, winning four premierships.

In front of the TV that Sunday, still at Primary School but already aware of the limits of my sporting prowess, I decided that’s what I wanted to be. A Student of the Game, not because I could see any future career for myself, but because I loved it, and wanted to learn as much as I could about the sport.

I kept exercise books of notes, with match reviews and player ratings, picking Richmond teams that could match-up against whoever we were playing that weekend. I would then scrutinise the teams when they appeared in the papers on Friday morning, often disappointed when the selectors disagreed with my musings, unaware as they were.

I also had a unique opportunity to explore the game across dimensions not available to many.

I would spend school holidays at the Punt Road Oval, home of the Tigers. Kevin Sheedy had taken his Student of the Game mindset a step further. He was still playing but had given up his trade as a plumber to become football’s first full-time Promotions Officer, taking the game to as many schools and clubs as possible, never tiring of the sport. When not out in the field, he was also based at Punt Road Oval and would come into Dad’s office in his yellow and black Richmond tracksuit, and the two would talk for what seemed like hours. I would sit silently and listen. These were cerebral discussions about the game, two football scholars challenging each other. They clearly enjoyed each other’s company and whatever football rabbit hole they found themselves in.

I started wandering into Kevin’s office and talking to him. The memories are vivid, with Kevin generously listening to me, and matching my regular inquisitions, not with answers, but questions.

”Who would you have played on Jesaulenko?”

“Why do you think we lost?”

“Who do you think is a better ruckman, Green, Balme, McKellar or Whale Roberts?

“What changes to the team would you make this week against Hawthorn?”

“Who would you play on Matthews?”

“Which players in the reserves do you think will make it?”

I also learned that if I had an opinion with Kevin, I best be able to back it up. Something thoughtful and considered, not just parroting what I’d heard from Dad or had read in the football media. I slowly built the confidence to offer more of my insight and arguments. Honest, and often unsparing in his assessment, Sheeds was happy to let me know, in a playful yet pointed manner, if I’d left myself short, never questioning my opinion, but my reason for having it.

He is still the same today when we catch up and talk footy and life.

There were others as well. At football social gatherings I’d go to with Dad, I’d shadow him, listening as they talked about the game. I also developed a good sense for those who would likely engage with me, and give me time. I just loved talking about the game and couldn’t get enough of it.

I also got to see the often vigorous, spirited and personal conversations between coaches, players and administrators when dealing with the complexities and ruthlessness of league football. Different views on the ‘how’, and mostly, but not always, in agreement on the ‘why’; what was best for the club. Relationships damaged, sometimes rebuilt, but often left to fester, never recovering.

Around a decade later, I get the opportunity to be the CEO of the club I loved. I often say Richmond FC saw something in me, which until that point, I had not seen in myself, and in many ways, still struggle to see today. I witness this often with the CEOs I now work with, voicelessly questioning their suitability and worthiness, even after years in the role.

We underestimate the value of our experiences, what we have learned and are learning, and most importantly, what capabilities and competencies we can leverage to build our CEO and leadership game.

The role of Recruiting Manager at Melbourne was a much better training ground for the position I was about to take on than I appreciated.

As Recruiting Manager, I was required to be strategic, assess talent, negotiate complex contracts and player trades, build relationships, teams and networks, and win buy-in from others, all excellent experiences. I learned how hard you had to work, not as a competitive advantage, but as an expectation. You could not allow yourself to be outworked.

I also made some bad errors and learned how to lick my wounds and move on. Critically, I also learned the importance of being organised, in my thinking, systems and my environment. I’d learned of a quote from the famous academic and writer Peter Drucker, from his book “The Effective Executive” published way back in 1966, where he says, “All the effective ones have had to learn to be effective”.

All things considered, very good training for a new CEO.

But it was never going to be enough. I quickly learned I had to become a student of different things, something other than being a Student of the Game, which until that time of my life, held no interest whatsoever.

As I sat in meetings with accountants, bankers and board members, staring down at the Richmond Football Club Balance Sheet and Profit and Loss Statements, the first time I had ever seen such documents, the blur of numbers fogged my brain. Even with my superficial and shallow understanding of what picture these documents were painting, the amount of red ink said as much as the furrowed brows of the men in the room. The club was no longer the powerhouse of my youth. It was broke and broken. Last on the ladder, owing millions, and losing millions meant that this famous club could die on our watch.

“What do I now need to be a student of?” I asked myself.

The answer was obvious, but overwhelming. I wrote down “Student of Business”, something that felt opaque and intimidating. It seemed a language and mindset spoken and understood by people so different to me. But I soon found common ground, the intersection between their lives and mine. I was able to relate to the performance aspects of business, forming relationships with those who enjoyed sport and its metaphor for business, particularly as it related to teams, leadership, developing talent, and decision-making in high-stakes and complex environments.

Whilst I still enjoy the almost nostalgic view of myself as a Student of the Game, I was, in fact, a Student of Performance, a journey that continues, focusing on the impact of leadership, particularly as it relates to the culture and behaviours required to achieve the goals we are collectively seeking to attain. I learned that in order to scale the organisation, you must first scale leadership, and I did so by leveraging what I had become good at and, not coincidently, what I enjoyed.

I would have four stints as an AFL club CEO over twenty-five years, all turnaround situations, not by design on my part, but because they were looking for CEOs because of their difficulties, and, I was never ready.

My father died during my time at Richmond. He was only fifty-two, and I was twenty-nine. We still had a lot of talking to do. With each new challenge I was presented over the next twenty years, as I considered the role and my worthiness, his words would come to mind:

“If it was a very good job Cam, they wouldn’t be asking you”.

Play on!

Stay Connected

Please subscribe to our “In the Arena” email.

From time to time to time we will email you with some leadership insights, as well as links to cool stuff that we’ve come across.

We will treat your information with respect and not take this privilege for granted.