Lesson #14 - Loyalty

Ron Barassi is being interviewed.

He is the most famous and celebrated player in the sport. He’d captained Melbourne to a Premiership only a few months earlier, his sixth in ten years.

He has just requested a transfer to the Carlton Football Club, where he has been offered the role of Captain/Coach.

It is the biggest story in the game, perhaps in its history.

As he will do several times in his career, Ron Barassi is changing the game.

“Where is your heart, Ron?” he is asked.

Ron Barassi puts his hand on his chest.

“Right here, Mike”, he says with a smile.

“Football wise?” is the follow-up question.

“Well, I think your heart is where you are at the time.”

Ron Barassi - The Carlton Premiership Coach

Robbie Flower was a beautiful footballer, a descriptor rarely used to describe anyone playing Australian Rules football. He is also the best player I watched ‘up-close’ in my 30 years in the game. I’m not saying he was the best I’ve seen, a different conversation, just the best I got to watch week in and week out as an insider, a different form of appreciation.

Sometimes when watching a game of sport, one player seems somehow different from any other on the ground. It goes beyond athleticism, skill, and competitiveness. It’s a rare combination and interaction of qualities and capabilities that set them apart. Without full access to any one element, they’d be reduced to mere mortals, just another player.

The superpowers of the great players are generally obvious, but with Robbie, it was subtle, almost inferred. He made subtlety his competitive advantage. Micro movements, both instinctive and studied, would bewilder opposition players, somehow finding himself in space, not just small spaces; it was like he had his own football and the MCG to himself.

As I watched “The Last Dance” on Netflix a couple of years ago, this thought came to mind. The show is a wonderful insight into the complexity and contradictions of high-performance sport and the balance between collegiality and accountability. It is also a reminder of the genius of Michael Jordan, who somehow manages to play at levels above the supreme standard of the NBA, such that the likes of Magic Johnson and Larry Bird are left shaking their heads.

If you listen to the commentary of Robbie’s era, words such as ‘graceful’, ‘elegant’ and ‘humble’ are used to describe, and it seemed, celebrate him. He was the Yin to football’s Yang at a time when brawn, brutality and bombast were mostly the marks of the 80’s footballer.

The game somehow needed him, and for this reason, while adored by supporters of the Melbourne Football Club, he was universally admired by anyone who loved the game, notwithstanding their club allegiance. Once a year, Robbie would belong to all Victorians, in State of Origin games, where we would get to fully appreciate his mastery when playing with and against the game’s best. He thrived.

For the Melbourne supporters of this era, their consolation was “at least we’ve got Robbie Flower” as they left the MCG after suffering another loss in the club’s most forlorn era. He was more than enough to bring them back next week, and for the best part of 15 years, almost the only reason Melbourne supporters would go to the football.

The lack of team success would be enough to challenge any team-oriented athlete, which Robbie undoubtedly was. There was no lack of opportunity for him to join the power clubs of his era. At a time when the faithfulness of players was being questioned as football lovers were coming to terms with the push towards professionalism, the Barassi move to Carlton seen as the catalyst, the pressure on players in poor-performing clubs to move to teams for riches and the promise of success was significant.

It seemed this was never an option for Robbie.

Soon the word ‘loyal’ was added to the other descriptors.

Former Western Bulldog champ and skipper Bob Murphy reminded me of Robbie Flower. He is the closest I’ve seen to him as a player, although I generally avoid comparisons between players as it is often an excuse for not adequately exploring the unique qualities of the individual player. Yet, I thought of Robbie Flower whenever I watched Bob Murphy play. Skinny, balanced and skilful wingers turned half-back wearing #2 might have been as deep as it went, but it was certainly there.

Having read Bob Murphy’s outstanding (and partly accidental leadership) book Leather Soul, this quote also reminded me of Robbie:

“It’s seemingly a fading currency in professional sport, or so I’m told. Loyalty in sport isn’t dead, just a little misrepresented. It’s not blind loyalty. Too much is at stake. The loyalty I’ve known in footy is a relationship – there must be an exchange of effort and goodwill. The Bulldogs and I were a good couple. I gave them everything I had. I hope they feel like they got a good deal, too. I’m a proud servant of the Bulldogs. Forever.”

Too often, leaders think of loyalty as an expectation, yet are unwilling to take personal responsibility for the relationship that created the less than optimal outcome – a good person leaving.

This is most apparent in times when competition for talent is amplified as it is now, but in actuality, genuine notions of loyalty are formed in tough times.

Winning is never the result of a single thing, but losing often is. Good culture is an artefact of our combined behaviours, particularly as it relates to building trusted relationships. The work leaders do when it’s hard will aggregate and be the reason they succeed in the future. Connections formed and established during challenging times will be the platform for loyal, trusted and high-performance relationships in years to come.

I remember discussing with Robbie why he never left Melbourne. His answer was simple.

“I always believed that one day we would get it right, and I couldn’t live with myself if I wasn’t a part of it”, he said.

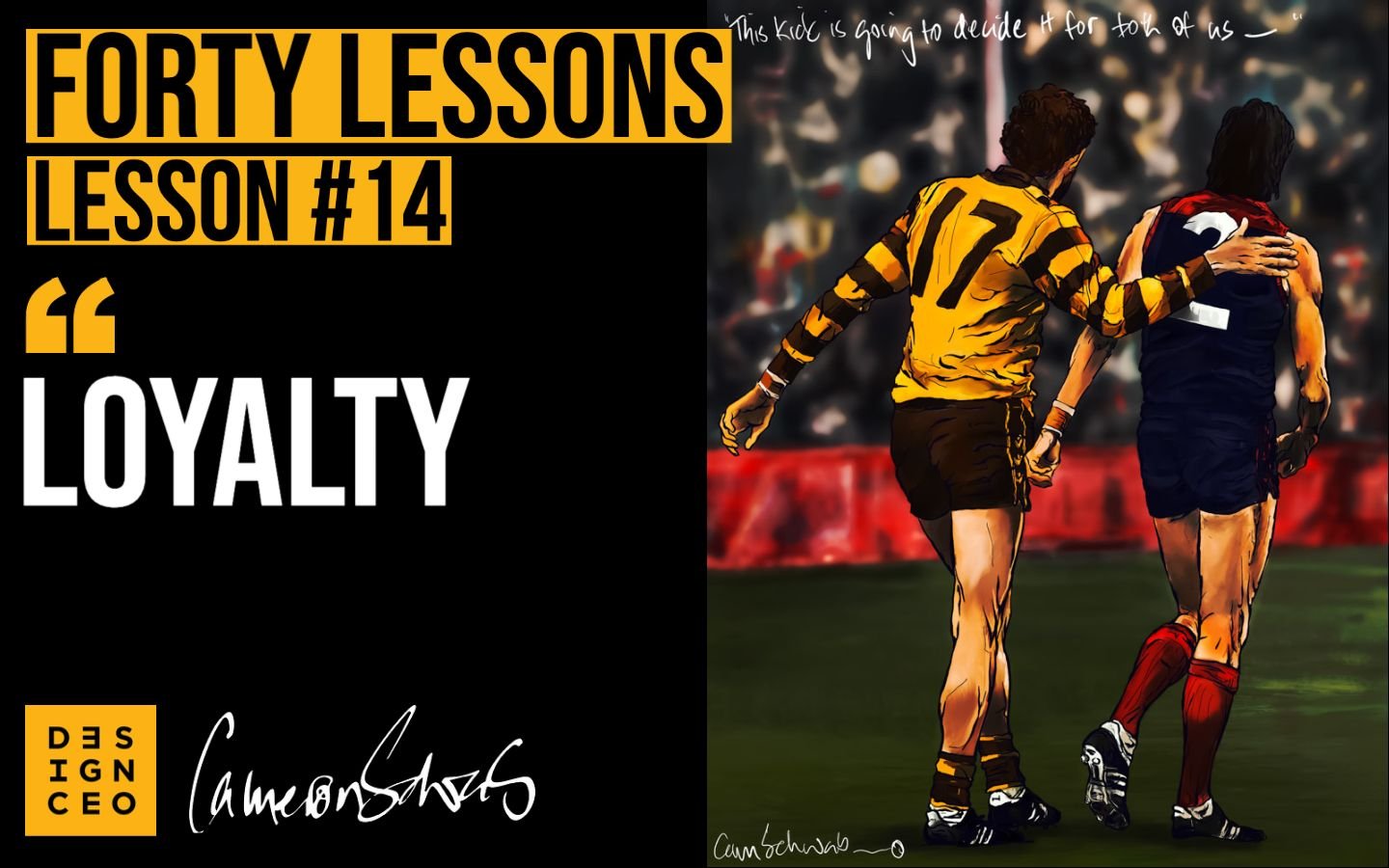

While Robbie never got to play in a Grand Final, his last three games were finals, the only finals he would play. He was captain of his beloved team, made up of youngsters who had taken the Demons to their first final series in twenty-three years, only to be beaten just one game short of the Grand Final by a superstar Hawthorn team with a Gary Buckenara kick after the siren in a folklore Preliminary Final.

I was Recruiting Manager at Melbourne at the time, and just a little bit proud to have played a small role in football lore, yet it remains the most heartbreaking game I was associated with. I have attempted to capture this emotion in my drawing of Robbie and Hawthorn champ and skipper Michael Tuck, the emptiness of missed opportunity.

Hawthorn Captain Michael Tuck and Robbie Flower

As long as the game is loved, people will talk about this game.

As long as the game is loved, Robbie Flower will be a hero of the Melbourne Football Club for all the right reasons.

In Bob Murphy’s words, Robbie Flower and Melbourne were a good couple.

“I always believed.”

Robbie Flower’s words go to the very heart of the concept of loyalty.

Melbourne was his club. It had been since he was a boy growing up in Murrumbeena in the heart of their old suburban zone. A Demon supporter from birth, he literally came through the ranks, the ’Boy’s Own Annual’ rise to senior football as a bespeckled, skinny 17-year-old who would soon be a star.

Believing and belonging are the basis of loyalty, and for Robbie Flower, they were mostly present for his career, despite winning only 30% of his games across fifteen seasons.

Knowing Robbie as I did, while humble and unassuming, this should never be mistaken for the fiercely determined and ambitious athlete he was. When most of his teammates had left the track, Robbie was always working on his game, perfecting his already beautifully honed skills, often on his own.

He also never lacked ambition for his team. He desperately wanted to be part of a successful group, and I have no doubt he had many moments across his career when he questioned whether that could be at Melbourne.

For any player, the football clock is ticking. The game waits for no one. With each game and season, Robbie was looking on as players from other clubs enjoyed the spoils of September Finals action and winning Premierships, players of far less capability and likely commitment than he.

His belief would have been tested often. He played with inferior teams and would have looked around the locker room knowing that there was not the quality to achieve what he desperately wanted.

But maybe next year?

It would’ve been enough for most to question whether loyalty was blind or had run its course.

Clearly, this relationship works both ways. Clubs constantly weigh up how they can improve their team, and if they have an asset on their list, one that is perhaps more valued by the market than they do themselves, they will always entertain the possibility of trading that asset.

As Robbie would have done, there would have been times, particularly towards the end of his career, where the club weighed up the potential trade value of their aging champion, perhaps a club in the Premiership window, looking to top-up for a shot at the silverware.

As it turned out, Robbie Flower was a forever Demon, and the game, and I suspect Robbie himself, was better for it.

Loyalty is a vexed question, and at times I have struggled with its expectations, real and perceived. What it actually is, and how much it really matters.

For some, loyalty is binary. You are either one of us or not, in or out, hero or villain. The emotion of sport plays to this, for some, including the media, helps create this narrative, or amplify it.

An example is the booing of ex-players, even those who left at the behest of the club, whose preference was to stay, but playing elsewhere was the only option.

Just seeing a player who once wore your club’s colours now wearing someone else’s, is enough to elicit this behaviour. As players prepare for a game against their old club, they know what to expect. The same people who once cheered them will now jeer them.

I have never really understood booing, and as we have experienced with Adam Goodes, when the game betrayed him, the damage can be such that it can never be repaired.

Those who somehow contrived to justify booing Adam Goodes as something other than being racially motivated were joining a chorus of those who clearly were, and in doing so, became one of them.

At the very least, and by any definition, it is workplace bullying. The worst kind, where the person being bullied has no defence.

Continually booing someone for what you perceive as a lack of loyalty constitutes bullying. I’ve seen first-hand how upsetting this is for some players and their families, forever changing their relationship with the game itself.

Loyalty can also be weaponised by employers, including football clubs. A form of guilt-tripping someone to stay, potentially making a choice that is not in their best interests.

Jeff Hogg - A Wonderful player in tough times

As a club CEO, I have been accused of lacking loyalty.

As CEO of the Richmond Football Club, I was involved in trading our captain, Jeff Hogg, to Fitzroy. Hoggy was an excellent Richmond player, a shining light in an otherwise desolate Tiger era. He was also a lifelong Richmond supporter, who, like Robbie Flower, came through the ranks.

Jeff was devastated when the trade was done, as were many Tiger supporters. I remember receiving child-sized Richmond jumpers with Jeff’s number 34 on the back with letters from fathers asking how they explain to their kids that their hero is now playing for Fitzroy because their club didn’t want him anymore.

Measured over time, this trade worked well in Richmond’s favour, but certainly not for Jeff, who struggled with injury, playing 40 more games but never being able to make the impact he had during his career at Richmond. His time also coincided with the last traumatic years of Fitzroy in the AFL.

There is, however, part of me that still questions, all these years later, our motivation and whether it was the right thing to do.

So what role does loyalty play in our decision-making from either side of the fence?

The answer is ambiguous and nuanced, not to be ignored, but never to be amplified.

Leaders in performance-based organisations will be responsible for change, and decisions related to personnel are embedded in this. Their history in the organisation is one of many considerations, but understanding all relationships will eventually end.

I think it starts with a double-barreled question that goes to the heart of understanding the vexed notion of loyalty and its place in high-performance environments.

“Do you believe in your people, and do they believe in you?’

Should the conditions of mutuality and belief exist, in my experience, so does loyalty. Without it, loyalty becomes dogma, driven by something other than what’s in everyone’s best interests.

In high-performance environments, there is what Sport Performance Psychologist Dr Michael Gevais describes as the ‘invisible handshake’.

When you are in a team environment, one with high standards, high pressure, and high stress, which is outcome-based, there must exist strong relationships, a sense of identity, a feeling of belonging, clarity of purpose, positive ways and systems as to how we best work with each other, to create positive collective outcomes.

But when someone metaphorically ‘fumbles the ball’ too often, it hurts the collective. If they just can’t get it done for whatever reason, regardless of their wonderful character attributes and hard work, they can no longer be a member of the team.

This is most difficult for those, who could once get it done, but for reasons often beyond their control, can no longer get it done.

Time waits for no one.

A loyalty framework.

Like most frameworks, they are never perfect. They are best used to inform decision making, providing the context, the team environment you seek to build, and content, information specific to the individual.

I will start with the content (the individual) to help inform the context (the team).

In terms of the individual, this assessment framework is derived from high-performance sport, its origins going back to when I cut my teeth as recruiting manager of the Melbourne Football Club, my first serious leadership role.

As Recruiting Manager, you are not only required to assess the player’s capacity now, but also make a projection as to their future capacity, and with that, a plan and process for them to achieve it.

The assessment framework builds on the mathematically flawed (but you get the idea) equation of:

Character + Capability = Connection.

Simply, you will not be able to maintain connection with individuals you do not believe have the character and capability to fulfil the fundamental expectations of the role, or do not have the future potential to achieve it, in a time frame that works for you.

The assessment framework is based on the question:

“What does the role expect of me?”, defined over the three dimensions of character, capability and connection as follows:

Character.

Ethos

How the person shows up, their work ethic, attitude, motivation, preparedness, humility, energy, focus and consistency.

Mindset

The curiosity to learn and courage to unlearn, take responsibility for their personal development, own their mistakes, and learn from them.

Capability

Skills

More than talent. Skills are an expression of talent as it relates to the specifics of the role. The requisite aptitude to perform the core expectations of the position, or be on track to have them. Also described as functional capability. The list should be no longer than 5-6 skills or categories of skills. For those in leadership roles, think of leadership as a skill.

Track Record

Getting ‘rubber on the road’, assuming reasonable timeframes and requisite support and resourcing, the person is building a track record regarding role expectations. Anything longer than 12 months usually is problematic.

Connection

Relationships

The most critical measurable in any organisation is the quality of relationships, with each individual required to establish mutuality and respect central to the organisation’s performance. Assume each person has at least five key relationships.

Buy-in

Deep commitment to the organisation’s purpose, culture, and strategy.

The context is where the person fits into the framework of the team. I do this by simply asking the leader this question:

“If we were sitting in a room three years from now, celebrating an important milestone, with things going well and you are on track to achieve your strategic and cultural objectives, who do you have in the room with you?”

Put four columns across the page, and list your current team into one of four categories:

Column 1 – Yes.

You would be disappointed if they were not in the room, such is their character, capability and connection. While no one is indispensable, these are the people you are building around.

Column 2 – Yes, maybe

You hope they are in the room as their development, potential, and growth has now been realised or is being realised.

Column 3 – No

You do not want them in the room, and you need to make a call as soon as possible based on the person’s character, capability, or lack of preparedness to connect with the team or organisation.

Column 4 – Respect

You have invited them back into the room because they played an important role in the team, and it was important they are recognised for what they brought to the team, even if they were unable to see it through for whatever reason.

I thought of Ron Barassi when legendary coach Alastair Clarkson recently chose to coach North Melbourne, the club he played for.

The Barassi move from Melbourne to Carlton in 1964 is still talked about as the “beginning of the end” of loyalty to club, when in reality, loyalty only went one way.

The transfer rules of the time really consisted of the clubs holding power over their players, which would slowly change over the next few decades.

Barassi had played over 200 games and won six Premierships with Melbourne when he sought a clearance to Carlton. He had well and truly paid his dues.

When asked, “Where is your heart, Ron?” and he puts his hand on his chest, we understand that wherever Ron’s heart was, he delivered.

When he finally retired from the game, he would be a Life Member of four AFL clubs. Melbourne, Carlton, North Melbourne, and the Sydney Swans, all of whom claim him, or at least a part of him, as theirs.

Knowing Alastair Clarkson, the opportunity to coach the club that shaped him as a young man was powerful, but not as much as the intense homework he would have done on the club, particularly its leadership.

North Melbourne President Dr Sonja Hood led the process and called on respected North Melbourne people to speak with Alastair. When announced as coach, Clarko spoke of both, his deep personal connection, but also the months of “due diligence”, and the confidence he gained from learning about his old club as it currently stands. He found clarity in their vision for the future, and the role he could play in it.

The other club vying for his services, Essendon, whilst a much bigger club and ostensibly a more attractive option, came late with a messy and chaotic approach, offered neither connection nor clarity, revealing a divided club, prepared to be disloyal to their incumbent coach for the slim possibility of convincing a high-profile candidate.

The decision for Clarko made itself.

This is what loyalty looks like.

Alastair Clarkson - Back at North Melbourne with President Dr Sonja Hood

Play on!

Stay Connected

Please subscribe to our “In the Arena” email.

From time to time to time we will email you with some leadership insights, as well as links to cool stuff that we’ve come across.

We will treat your information with respect and not take this privilege for granted.