Lesson #19 - Constraints make the art possible

I enjoy a creative backstory.

To draw the energy or inspiration from somewhere to bring something into existence that was not there before.

Leaders are creatives but mostly do not think of themselves as such.

Legendary music producer Rick Rubin, in his book ‘The Creative Act – A Way of Being’, described the process of creativity as follows:

“Regardless of whether or not we’re formally making art, we are all living as artists. We perceive, filter, and collect data, then curate an experience for ourselves and others based on this information set. Whether we do this consciously or unconsciously, by the mere fact of being alive, we are active participants in the ongoing process of creation.”

Rick’s take sounds a lot like leadership. When coaching leaders facing into ambiguity and complexity, I talk about the dimensions of data, dialogue, then decision, knowing all will be imperfect, inadequate, and insufficient, the very reason we need leadership in the first place.

As a coach, I encourage leaders to shift from a mindset of reaction to reflection.

This can be challenging. Leaders often draw their energy from their reactions, the vitality of high-stakes decision-making and its associated urgency, real or perceived. This instinct has generally served them well, received recognition and formed part of their ascension into leadership roles. Reflection means slowing down to ‘curate’ thinking, and not only does this run counter to self-perception, but also an embedded belief of what the role expects of them in these situations.

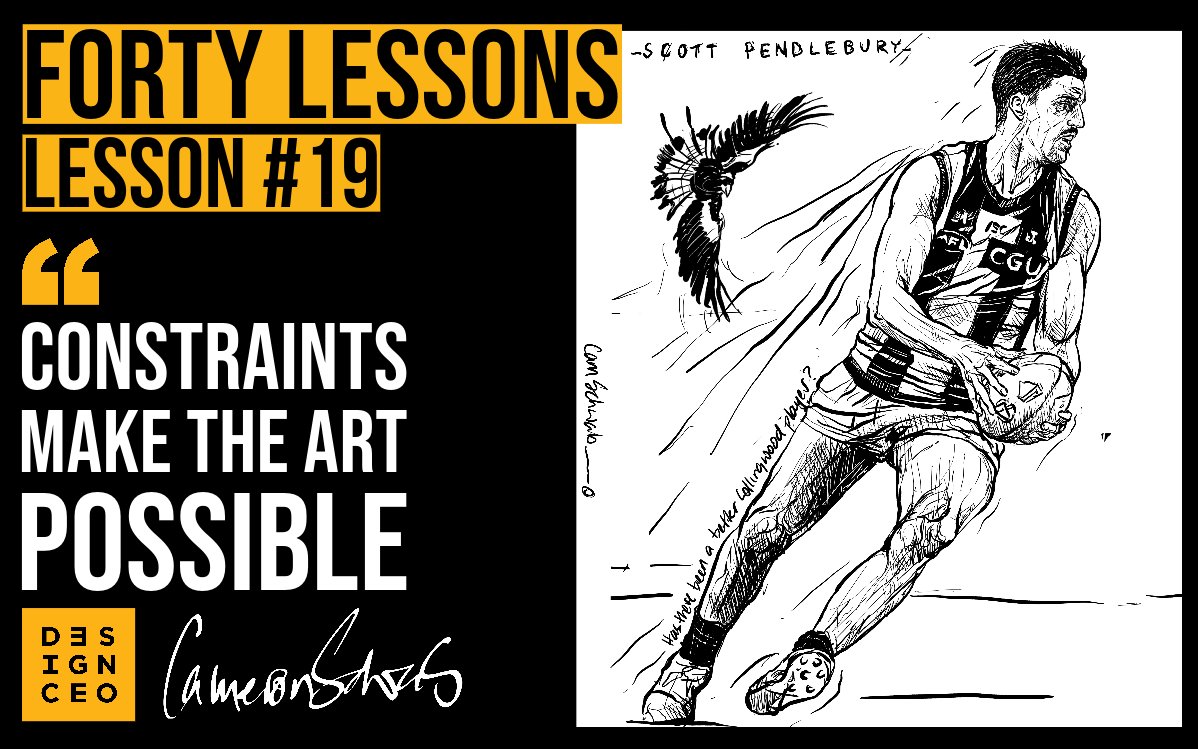

To illustrate the point, I will speak of the great athletes who can ‘slow’ the game down in the absolute heat of battle, allowing the extra milli-second to ‘curate’ their options with the ball in hand. Collingwood superstar Scott Pendlebury is AFL football’s best example of this. For him, the constraints of the moment, in the middle of the MCG, with a million eyeballs watching and judging, make his art possible, as he did on Grand Final Day in 2023, particularly in the last quarter when it mattered most.

I was listening to Performance Psychologist Dr Michael Gervais interview the musician Moby on his ‘Finding Mastery’ podcast, the coming together of two wonderful thinkers, one from the domain of elite sport performance, the other who has spent three decades continually evolving and beating on his craft, refusing to be labelled, yet always seeming to be at the top his game, that reminded me of the importance of constraints and creativity.

“What stands in the way, becomes the way”, Stoic philosopher Ryan Holiday espouses, or more specifically, “The obstacle is the way”.

In the ‘Finding Mastery’ interview, Moby openly describes himself as an alcoholic, although he has been sober for fifteen years. He did the 12-Steps with Alcoholics Anonymous (AA).

He talked about hitting rock bottom – date, time and place forever embedded in his subconscious.

“It was October 8th, 2008, and I had played a fundraiser for a politician in upstate New York, and I, of course, had my 25 drinks afterwards and found someone to sell me terrible rotgut cocaine. And I was taking the train back into the city, and I couldn’t think, I couldn’t read, I couldn’t look out the windows. I was so hungover and sick. And I realised I’d felt that way every single day for the last eight years. And all of a sudden, I was like, “Oh, it’s not getting better. I’ve tried to strategise my way around this, but it’s just simply not getting better. It was just simply, as Steven Tyler from Aerosmith said, I just unrelentingly sick and tired of being unrelentingly sick and tired.”

He spoke of the wisdom gained from AA, particularly those he shared the experience with, some of whom became mentors and talked to their insights. There was one concept that strongly resonated with me:

“One of my friends from the program said something that I loved, and it’s so simple. “We’re either moving towards a drink or away from a drink,” and you can replace drink with anything. Like we’re either moving towards anxiety or away from anxiety, I’m moving toward bad habits or away from bad habits, I’m moving towards anger or away from anger.”

I noted:

“We are all moving towards or away from something”.

—

About a decade ago, I was sacked as CEO of the Melbourne Football Club. This life event forced me into a place of deeper reflection, mainly as it related to identity. I’d been the CEO of an AFL club for most of the previous 25 years, over half of my life.

I have spoken previously about clinical depression, diagnosed in my mid-30s. One of the books I read to try to make ‘sense’ of depression was Andrew Solomon’s ‘Noonday Demon’. In the book he writes, “Grief is depression in proportion to circumstance; depression is grief out of proportion to circumstance.”

While my life had just changed dramatically due to a decision made for me, rather than by me, I understood this reality. As a CEO in elite sport, cut-throat by nature, I had made many similar decisions, never fully understanding the impact on the individual. It was also not the first time it had happened to me, some fifteen years earlier, and this was when I was first diagnosed with depression.

I was determined to keep my grief in proportion, fearing a relapse.

In my study and reading, I chanced upon the Aristotelian concept of ‘A Good Life’ and, given the changes I was in the midst of, spent some time attempting to bring definition to the idea.

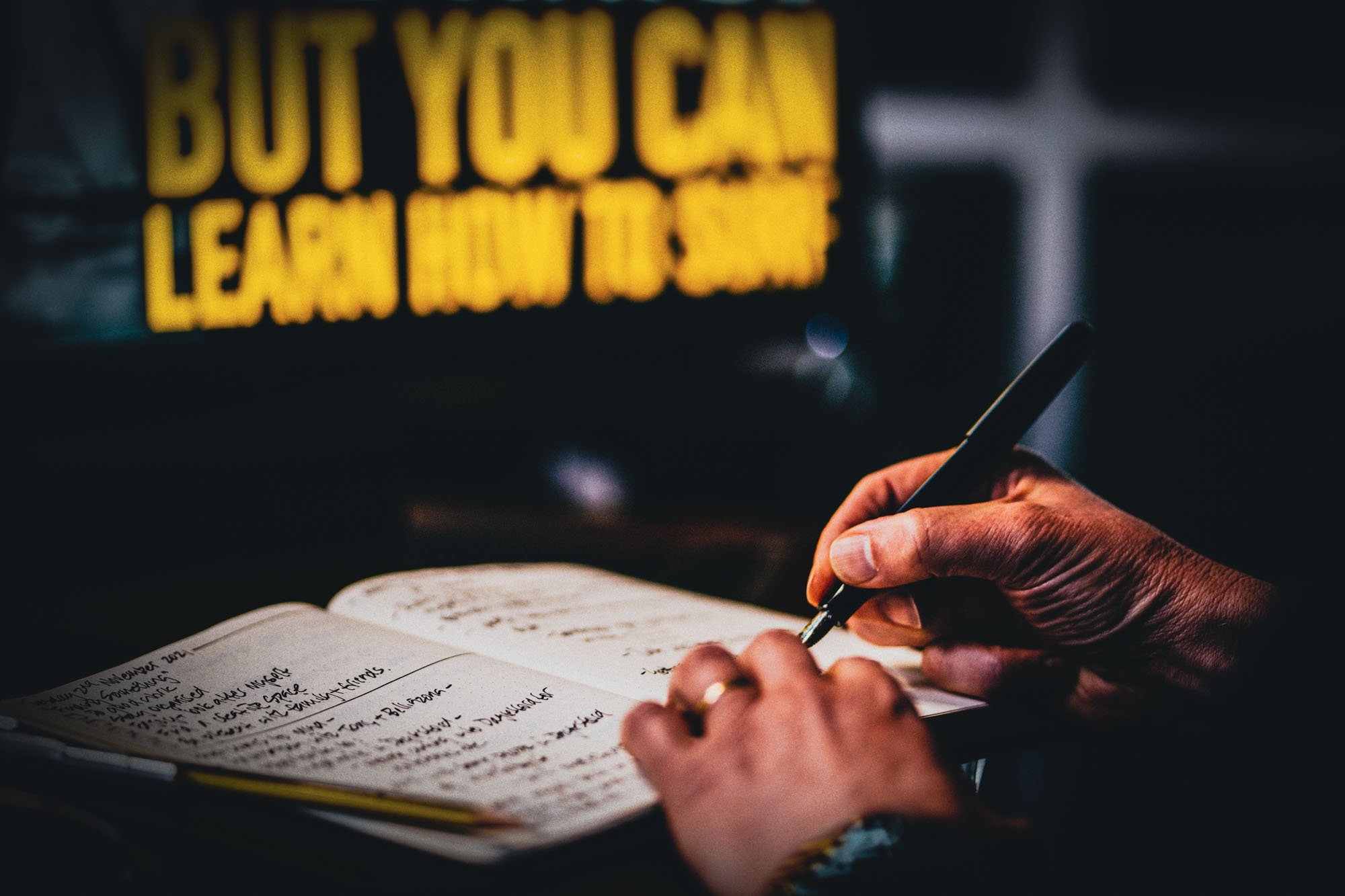

One of my favourite concepts is “If you are underthinking, read – if you are overthinking, write”. In my experience, reflection doesn’t happen unless pen is hitting paper.

It was quite some time after I was diagnosed that I finally found the will, with the love and support of my family, particularly my wife Cecily, to learn as much as possible about depression. I sought the wisdom of mentors, trusted people in my circle (i.e. conversations with wise people) and those whom I will likely never meet but who had the courage to tell their story and ‘ship their work’ (i.e. write a book). Still, I understood the sense-making will only happen when the writing starts.

One of my mentors for many years was the great coach Allan Jeans, who once reminded me, in the most emphatic yet empathic way, “It’s not how you get knocked down, it is how you get up”.

“Everybody needs a hero”, and such was my respect for the man, his words became my intention and a mantra. I started writing them at the top of the page every day next to the day’s date. But in time, I realised it needed to be more than a will to get up, and it soon became a pursuit of a means and an understanding of what could conceivably drop me to my knees in the future as depression had done.

I needed to find something. In time, I started writing ‘Finding Something’ at the top of the page and have done so for over twenty years. It is what I call a ‘trademark’, and the simple act of writing it down daily reminds me of the person I seek to be.

Back to Aristotle and his ‘Good Life’. Clearly, there are domains and dimensions to our lives, such as our work, loves, health, and their many overlaps and interrelationships.

These I have now defined and write down every day in the form of statements that have just enough expectation embedded in them, against the context of ‘Finding Something’.

They are, in no particular order:

Enjoy and look after myself

Be present with family and friends

Do good work

Find a creative space

Stay organised

After listening to the Moby podcast, I was writing some notes and, taken by the concept of “moving toward or away from something”, decided to run this lens over each of the above domains. It was enlightening.

In doing so, I (re)discovered two things:

The importance of confronting, and in doing such, replacing what seems to matter with what truly matters. Like many people, I start my days with a ‘To-Do’ list, but I realised that the seems to matter items, noisy and unambiguous, had become an excuse for not confronting the stuff that truly matters, the latter quietly ticking away at my subconscious, a dull ache, but never featuring on my ‘To-Do’ list, out of sight, but not really out of mind.

The power of progress, particularly as it relates to motivation. Too often, I allow a perception of perfectionism to blunt progress, and I know I am not alone in this regard. Some progress is better than no progress, and progress is far more important than perfection.

Those who have read my work know that I am more into ‘system setting’ than ‘goal setting’, and having experienced the value of the impromptu system that I created, I have now put this into practice with the leaders I work with.

It starts with two columns headed up with the questions:

What do I need to confront?

What do I want to confront?

Study your responses, and put an asterisk next to the two items in each column that most demand your attention. Now ask yourself two more questions:

What am I going to do?

How do I make it happen?

In regard to the final two questions, remember, it is not about doing more, it is about doing different. You will need to make tradeoffs and overcome resistance in its many forms, to make progress and move ‘towards’ a potential outcome.

My reflection on the idea of ‘A Good Life’ using this ‘system’ had a very surprising consequence.

It revealed the importance of creativity to my energy, and even within the constraints of a CEO position, it was always the aspect of the role that I enjoyed most and where I made the greatest impact.

It was the constraints that made the art possible.

When teasing out ideas around “Find a creative space”, I wrote down:

“I like to draw”.

If I was doing this exercise now, it would have soon had an asterisk next to it. I started searching, or it could be better described as confronting both a need and a want, then establishing what I was going to do, and how I would make it happen.

What options were available to people like me trying to determine whether they have an itch, and how do they scratch it?

The next day, and a few tram rides later, I am at the Northern College of the Arts and Technology (NCAT) in Preston, sitting down with the compassionate, straight-talking and gifted art teacher Tracy Paterson, having a conversation I never thought I’d have. Half an hour later, I’d signed up for a 12-month Certificate IV TAFE course called ‘Folio Preparation’.

On the way home, I rang my wife Cecily to tell her what I’d done, and she said it was the most joy she had heard in my voice for years.

This led to studying Fine Art at the Victorian College of the Arts (VCA) a year later.

At the VCA, I came across the stunning work of sculptor Elizabeth King. In reading about her work, I saw a quote, “Process saves us from the poverty of our intentions”.

It is the constraints that make the art possible.

Elizabeth King’s language is rather theatrical, as is her work, but it spoke to ideas of purpose at a time when I was redefining and redesigning my version of this after thirty years in the AFL, a process that led me to art in the first place. When I read this quote, studying fine art suddenly didn’t seem that different. While the narrative of elite sport is club vs club, or team vs team, for those inside the organisations, it is system vs system, and now I am seeing how it applies to the pure process of creativity – the actual making of art.

It was at the VCA, at a time I was struggling with all of the things artists struggle with, often referred to as the ‘muse’, a mystical creative force more powerful than us, such that I really couldn’t refer to myself as an ‘artist’, a moniker way too highfalutin, an amplification of my day-to-day reality of staring at a blank canvas, and all of its intimidation.

I often felt like this in my previous life, struggling to call myself a leader when my day-to-day experience, reality, and what I was offering, felt unworthy of this tag.

I realised that to create, I needed to design the conditions for creativity.

I thought about the times as a child when I could sit for hours and draw. My only ‘tools’ were my grandfather’s thick, black tradie pencils and butcher paper, and the only thing I was interested in drawing were the footballers who had captured my young imagination. I’d draw pictures of Richmond players taking impossible marks, going all angles, looking more like superheroes than mortals, an accurate representation of my young imagination, inspiration and inventiveness.

They again became my tools.

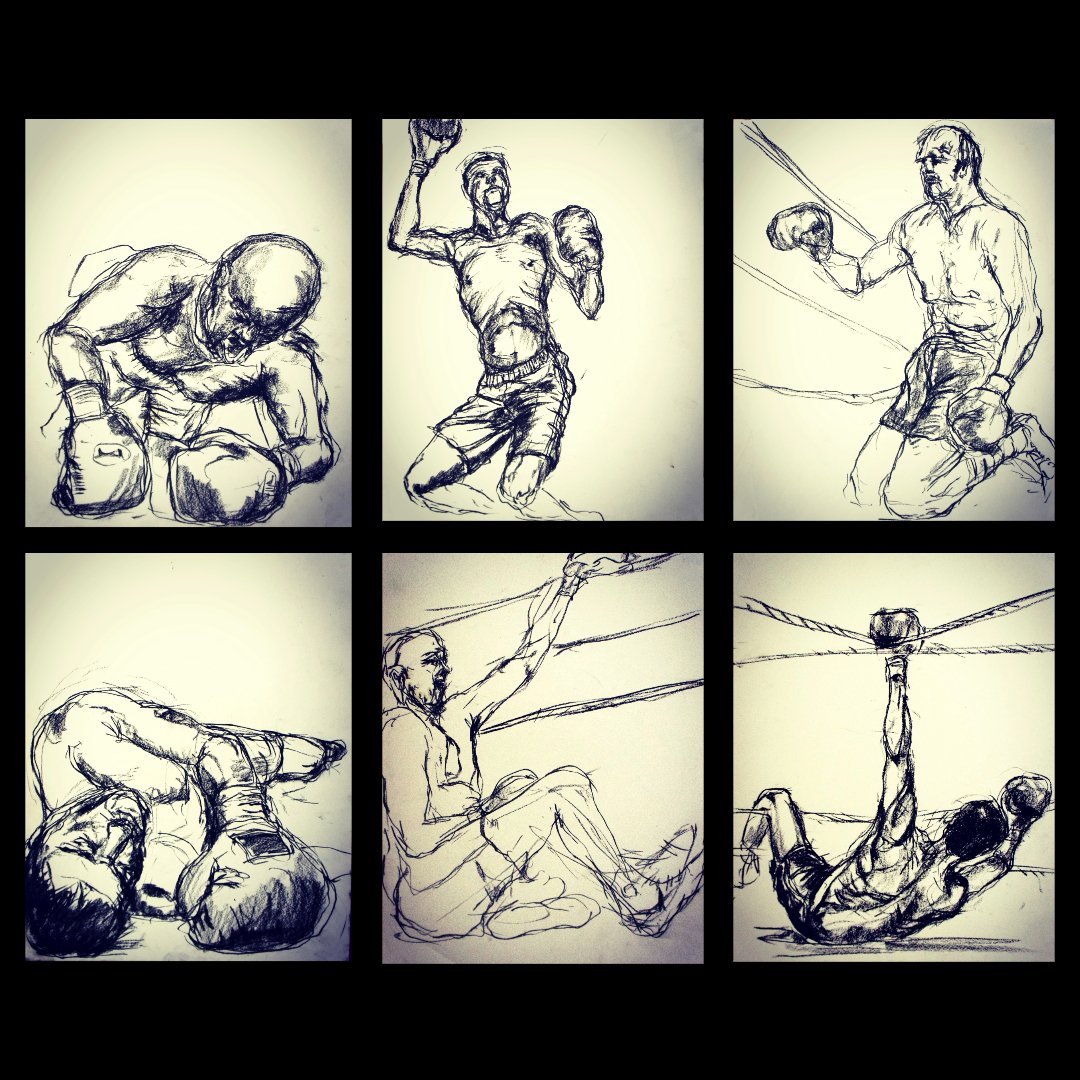

I wanted to express my Trademark, “Finding Something”, and whilst I am not a fan, the sport that best represents the “Not how you get knocked down, it is how you get up” mantra is boxing, inspired no doubt by watching ‘Rocky’ when I was a kid, still my favourite ever movie.

For the drawings, I deliberately constrained three components:

One subject matter, boxing

Two ‘tools’, butcher paper and a thick Blackwing pencil

Three ‘rounds’ for each drawing, for a total of nine minutes

The drawings are very rough, but they achieved the outcome I sought regarding their expressiveness. I am almost sure this would have been lost if I’d given myself more time, tools, or colours to work with.

It was the constraints that made the art possible.

I also regained some confidence from the exercise and did some of my best work from then on. I also discovered that the ‘muse’ is not a mythical concept, but will visit you when you have a system and you do the reps.

Deliberately creating constraints forces deeper thinking and innovation, and this act moves us towards ‘something’, a self-saucing kind of motivation that we all need from time to time.

Your time, energy and attention are your most constrained resource. When used wisely, the art will happen.

Go make some art.

Play on!

Stay Connected

Please subscribe to our “In the Arena” email.

From time to time to time we will email you with some leadership insights, as well as links to cool stuff that we’ve come across.

We will treat your information with respect and not take this privilege for granted.