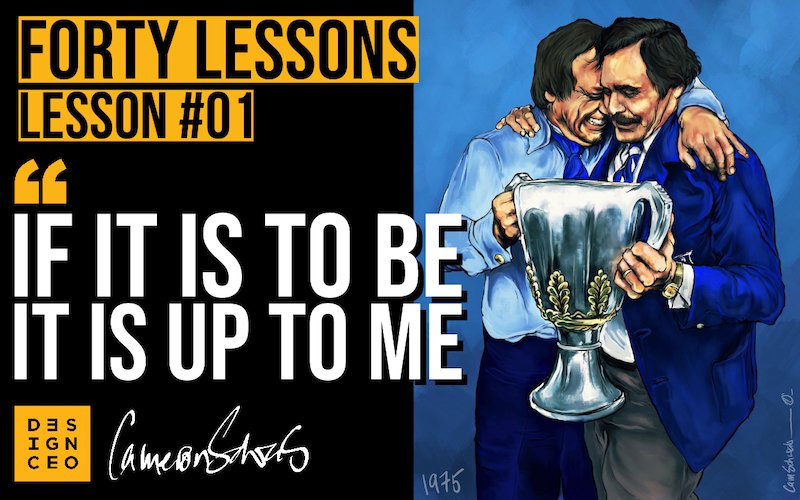

Lesson #01 (Reprise) - Ron Barassi: “If it is to be, it is up to me”

Some dates will always stay in our minds.

Embedded deep in our consciousness.

As the calendar turns, it takes you somewhere, back to a time, and most likely a place, person or people.

It might be a world event. Whenever 8 December comes around each year, I think of John Lennon and my suburban bedroom, listening to radio station 92.3 EON-FM, with FM radio just becoming a thing. I learned that my musical, spiritual and philosophical hero had been shot dead in New York.

As the breathless words entered the room via my clock radio, there was too much information to draw in. It was like a Catherine Wheel had been lit in my teenage bedroom, spluttering senseless sparks in every direction.

There are personal events. Your first date with the person you would spend the rest of your life with, or the day someone special leaves your world. My grandfather, who we called Puppy, died suddenly from a stroke on the 11th of June. He was my Mum’s dad, and we were close. Puppy taught me how to draw. Thick tradie pencils on butcher paper. We’d draw horses. I still draw horses.

It was my first personal experience of death, loss and grieving.

He was a willing, conscientious, yet slightly taciturn man. When he was gone, my overwhelming feeling was we still had talking to do.

Puppy died the same year as John Lennon, and they will always be connected in my world.

January 11 is one of those dates for me, the day I joined the workforce. I went straight from school to work, deferring a so-so offer to go to university after Year 12, with no real plan and indeed little idea, but somehow knowing it was the start of the rest of my life.

I’d completed school a month or so earlier. With a newly minted driver’s licence I’d got on my 18th birthday and a 1970 Mazda 808 bought from a local car yard owned by one of Dad’s football buddies, I went away to Anglesea with a few mates and my girlfriend, knowing that the countdown was on, to a place of transition, stepping into adulthood, each on their own path.

Most of the group had a couple of months of sun and sand ahead of them as they were heading off to various universities, whereas I didn’t know whether I was skipping or avoiding what was becoming an expectation beyond high school.

“You need something to fall back on. Gotta get a trade or an education,” was the prevailing wisdom of the time, and it seemed that I was not equipped nor motivated by either.

I had gotten myself a job, not by design but by circumstance, which represented neither trade nor education but, in time, would be both.

I’d spent the best part of six hours standing on my own in the visitors’ player race at Moorabbin Oval, the home ground of the St Kilda Football Club.

My feet were numb from the cold and wet bitumen. It is winter in Melbourne, and this part of the world has its own chill factor. The bitumen morphs seamlessly into a squelch of black mud, a section where grass will never grow, evidenced by the perfect imprint of the last studded boot that made its way out onto the ground.

There is no lack of activity in the race as people go about their business with purpose, the day punctuated with fits of activity in response to whatever was occurring just metres from where I stand. Melbourne is playing St Kilda, last versus second last, and the Demons are getting towelled up.

The smell of the sludge is redolent of any of the suburban grounds I’ve played footy on since I was five years of age, familiar yet offering scant comfort as, in every other sense, I feel the outsider, in the road, as though I am being imposed on a group suspicious of the son of the league bigwig.

I look like the work experience kid. The private-school boy, right down to the flick-back Travolta haircut, navy-blue blazer, white shirt and tie, grey pants and shiny black lace-ups. It is the same silhouette of the school uniform I’ve worn for the previous six years at Camberwell Grammar.

The only real difference is the tie. It was royal blue, with two thin red stripes which bracketed three intertwined letters in the timeless typeface of a thousand old-worldy sporting clubs.

The letters are the M, F and C of the Melbourne Football Club, the most old-worldy of all football clubs, still playing the game it invented 120 years earlier.

I’d spent some time the previous night preparing for this day. Nuggeting shoes and ironing creases out of the just-unboxed Pelaco shirt. But it was the tie I’d spent the most time on. Half an hour of tying and re-tying, getting the length right and positioned such that the monogram sat mid-chest, each time I checked myself in the mirror. After many attempts and achieving this outcome, I loosened it to slide the still-knotted anachronism over my head, prepared and ready for the next day.

I wanted to make the right impression and could not think of any other way to do so other than to look the part.

“If you can’t play like a footballer, at least look like one,” my junior coaches would say.

“Jumpers tucked. Socks up, and clean your boots.”

The tie had been given to me that week by Dick Seddon (pictured right), the Executive Director of the Melbourne Football Club. He did so with ceremony, even though it was just the two of us in his office, a large room with an open fireplace in an old terrace house in Jolimont, overlooking Yarra Park and just a few hundred metres from the MCG.

Having made my way into Jolimont on the train, arriving at the station a good hour before the required time, I’d killed time by walking laps around the outside of the MCG. I was desperately nervous. I could feel myself shaking. I was hoping it was the cold Melbourne June day and my walk would settle me.

This is the first job interview of my life. I am seventeen, halfway through my final year at high school. A few weeks earlier, a job advertisement had appeared in the Melbourne Sun newspaper and I’d applied. The Melbourne Football Club was seeking to employ a junior administrator, with the only prerequisites being a demonstrable love of the game, a preparedness to work long hours, HSC (Year 12) and a driver’s licence.

It was not until this advertisement appeared in the paper that I considered working in football. This, even though the game had been the constant in my life, which I was able to live vicariously through my father Alan. After a highly successful career as a club leader, including four Premierships at Richmond and St Kilda, Dad was now a senior executive at the VFL.

Such was the pedestal I’d put my father on, the possibility of having a role in the game was one that I considered to be beyond me.

When I spoke to Dad about the role, he asked, “Are you prepared to work hard?”

I could only say ‘Yes,” with some understanding of the expectation, the lived experience of a child who saw a lot less of his father growing up than any of his mates, his absence from the home I attributed to the demands of the uncompromising world of elite sport. If pressed, however, I knew I couldn’t back it up. I had no track record of dedicated and concerted effort which I am sure is the reason he asked the question in the first place.

Dad would have been confident I had enough of the basic tools, my school reports indicating I had some horsepower but highly variable application, and given we’d spent a lifetime talking football, he also recognised the benefits of my unique upbringing.

With few credentials beyond a respected football surname, I was appointed to the role, with the only proviso being I successfully negotiated my last few months of Year 12 and passed my driver’s test.

I was now officially the Assistant to the Football Manager of the Melbourne Football Club.

So short was my interview, only thirty minutes before Dick’s tie presentation, I had been sitting in the club’s reception, a space dominated by a large black-and-white photo of Norm Smith, the late and legendary Melbourne coach. The ‘Red Fox’ in action, earnest and imperious, coaching from ground level at the MCG. Norm’s old club blazer is displayed in an adjacent glass cabinet. Embroidered on its breast pocket above the MFC monogram are the numbers 55, 56, 57, 59, 60 and 64, the six Premierships teams he coached, the dynasty he led.

Norm’s image watches over in judgement of those who enter his football club. They are responsible for carrying his legacy, although I doubt he would see it this way. It is proving a heavy burden and getting weightier by the year. At the time I joined the club, no Melbourne team had made the finals since Norm was famously sacked just months after coaching them to the 1964 Premiership.

The context is not lost on me. The last Demon Premiership was a few months before my first birthday.

But there is reason for excitement and optimism at the Demons. A year earlier, Ron Barassi, Norm’s Premiership Captain who had played in all six of his Premierships, his protege had, in a blaze of publicity, returned to his old club as senior coach.

Having left Melbourne after leading the Demons to the 1964 Premiership victory by just four points over their greatest rival, Collingwood, Ron went to Carlton as Captain-Coach in what may still be the biggest story in the history of Australian football. At a time when there was little movement of players between clubs, particularly the stars, Barassi to Carlton changes everything, a move that heralds the transition to professionalism from what was ostensibly an amateur sport.

Where Ron went, Premiership success followed. A twenty-one-year Premiership drought was broken at Carlton in 1968 and another Premiership followed two years later. That game, the 1970 Grand Final, is etched in the sport’s folklore. Barassi’s Carlton came from 44 points down at halftime against Collingwood, their coach instructing his players to handball and play-on, and with this famous victory, the modern running game was invented.

In six years, Ron Barassi had fundamentally shifted the sport, both on and off the field.

In 1973, Ron Barassi was appointed coach of North Melbourne, at that time, the only league club never to win a Grand Final. In his third season, North are Premiers, and two years later (my drawing right with the great North Melbourne man, former Club President Allen Aylett). They win another, again beating Collingwood in the Grand Final replay, having played a draw the week before.

Ron Barassi is now known universally as ‘Super Coach’.

His return to Melbourne also reminded the football world of Ron’s unique relationship with the Demons. Ron’s father, Ron Senior was a Melbourne Premiership player, friend and teammate of Norm Smith. He was the first league player killed in World War II in Tobruk in 1941, just months after his last game, the Demons’ 1940 Premiership when his son was only four years of age. Ron Jnr. lived with Norm Smith in his teenage years and was one of the first players recruited under the father-son rule, the Demons successfully lobbying the league to have first access to the son of their fallen Premiership and war hero.

When appointed coach of Melbourne at the end of the 1980 season, Ron Barassi had played or coached in 17 grand finals for 10 Premierships, including four as coach. Ironically, the three numbers add up to 31, the guernsey number both he and his father wore at Melbourne.

There has never been a bigger name in the game, and he is back at the club to continue a personal legacy that started 45 years earlier when Ron’s father, the young rover of Italian heritage from the gold mining town of Castlemaine, walked into the club.

It was Dick Seddon who had facilitated this coup, having assumed the role of Executive Director a year earlier. Sadly, Dick passed away just a few weeks ago. He was a wonderful man.

When explaining my role to me, and while my job description in those early days was typical of any office junior, Dick explained it more succinctly:

“Do anything Ron Barassi asks you to do.”

It might just be the best job description I’ve ever had.

The date came around as they thankfully do. Last year, 2022, marked forty years since I arrived way too early for my first day of work at 26 Jolimont Terrace, Jolimont, the offices of the Mighty Demons, sitting on the steps waiting for the first person to arrive.

There was no actual induction that I can recall. Still, I did have a desk in a small office which I shared with Ray Manley, the Football Manager, with whom I was the ‘Assistant to’, my soon-to-be printed business cards would declare, and Rosemary Long, Ron Barassi’s Assistant, a role she still played forty years later. Both would have a wonderful impact on me as I tried to negotiate the complex organism that is a professional football club, picking me up and straightening me up, often daily, as I tripped over my own feet.

Dates, places and people embedded in who I was and who I was becoming.

I do remember being presented with a very large ring of keys, one of which was for the office so I wouldn’t have to sit on the steps, but also, incredibly when I think about it, to the MCG itself. Having just turned 18, and with complete trust and without hesitation, I had in my daily possession the keys to one of the most famous sporting stadiums in the world.

In those days, Melbourne was still training at the MCG. The players, being part-time, arrived at training from around 4 pm, and one of my jobs was to open the rooms, stand with a clipboard, mark off the names as they arrived, and hand out the memos scheduling the next weeks of each player’s football life.

I would also pass on personal mail that had arrived at the club. Much loved captain Robert Flower would receive a daily lack-a-band bundle, most addressed with a kid’s scrawl to Robbie Flower, Demons, MCG, no address, postcode but the posties still knew how to facilitate its delivery.

I was also required to lock up after training, hence the keys.

Being January and cricket season, the Demons didn’t train on the MCG surface itself and wouldn’t do so until a week before round 1 of the football season in April. So players and support staff would make their way over the old railway footbridge to a large paddock known as Flinders Park opposite Olympic Park, a space now occupied by the Rod Laver Arena.

There were no ground markings, and the rough, dry ground had to be transformed into something that approximated a football ground with witches hats marking the boundary line and using the portable Little League goalposts banged into the hard turf.

Building this training ground was another of my jobs. In the early afternoon before training, I would drive into the MCG and load my car up, a bootful of witches hats and goalposts hanging out the window of my little car. With a measuring wheel that would click every metre as you pushed it, but required you to keep count, I’d use whatever mathematical prowess thirteen years of schooling had left me with and mark out an MCG-sized ground for training. This exercise would take at least a couple of hours and often in the heat of the Melbourne summer as my mates drank beers and caught waves on a peninsula somewhere.

Throughout this exercise, I considered myself the luckiest person in the world.

The test would be when Ron Barassi would arrive, jogging from the MCG in his football boots with his coaching staff. He’d stand in the middle of my newly created oval as the players did their warm-up, and size it up, often pacing it out or getting onto one knee, down to witches hat-level to check out the arc of the ‘boundary line’ that I had formed. With more than a bit of trepidation, I’d watch, his body language telling all.

The Barassi disposition never deceived his mood. It was there for all to see, and it was rarely moderate. Generous and deeply interested mostly, and often playful, but when it came to the training track, it was about exacting standards of professionalism, the ‘little things’, as he would call them. He would take in the environment with an intensity, moustachioed lip curled, barrel chest out, searching for any sign that a standard had slipped. Players would be sent off the training track for having a hole in a sock, ears ringing.

The Barassi ‘spray’ was legendary. In an era when all coaches had this arsenal in their coaching kit bag, Barass was trigger happy.

The spray was very much a one-way conversation. Rare was any form of response, a dropped head only making matters worse.

“Look at me when I am talking to you (name inserted),” he’d yell. “Do you even know what I am talking about?”

“Yes, Barass,” would be the response.

“Good, now go out and show me.”

Not just meant for the individual who made the error, the spray was a shot over the bow for anyone in earshot, mostly the player’s teammates. In elite team sport, feedback, assuming it is not personal, is mostly delivered in group settings, so everyone learns from the message. Team-based environments rely on this, both from a growth perspective and in support of each other. In strong cultures, team leaders will put their arm around the player who might be feeling a little wounded and isolated, but in a way that doesn’t compromise the message, seeking to reinforce the learnings while reassuring the individual that they’re a valued member of the team.

Wherever Barassi went, interest would follow.

In one of those early training sessions, a photographer snapped a photo of Barassi firing short passes with all of his usual competitive verve at one of his coaches, most likely the recently retired former Demon Captain, Stan Alves, who enjoyed taking on the best that Barassi could dish up, and returning fire. In my new uniform, a football in my hand, I am in the background of the photo standing with a languid teenage disposition. It would appear in The Sun newspaper a couple of days later, and I was more than a little chuffed (photo right).

The ground construction exercise would be my routine throughout the full pre-season, at least three days per week. But soon, the excitement and novelty began to wane. It just became hard and mundane work.

One sweltering afternoon, the same day as my photo had been in the paper, the famous Nylex Clock in Richmond showed the temperature well into the high 30s, with a fierce northerly blowing up dust as I laid down the cones and tried to bang the goalposts into the hard turf. My energy quickly waned and I discarded the measuring wheel and maths, convincing myself I did not need them as I’d completed the task a dozen times by then. I got the job done in half the time, and a glance at my watch confirmed I didn’t need to get back to the MCG to open up for another hour or so.

I jumped back in my car and headed up Swan Street, looking for somewhere to grab a cold can of sarsaparilla, my soft drink of choice. I found a park in front of a small cafe and bought my Sars. In the cafe, I noticed a pile of well-thumbed newspapers. On top, with the sports pages facing up was The Sun with my photo in it. I decided to sit down, pick up the paper, and feigning interest in something other than the sporting section, held it at an angle such that someone might recognise me as the young lad in the photo.

Nobody did.

Returning to my car, I realised something had changed. Swan Street had now choked with early peak hour traffic. I manoeuvred my car back into the traffic, unable to do the U-turn required to head in the direction of the MCG. Whilst only a few kilometres away, the stadium now seemed like a mirage through the simmering Melbourne traffic.

I tried ducking up one of the inner Richmond backstreets, but others had the same idea, and soon I was stationary again. I started to panic as I sat in my blazing car with vinyl seats and no air conditioning, not moving, knowing I was going to be late opening the rooms for the players and staff who would be arriving now, and I had no way of telling them, no mobile phones in those days.

It was now getting desperate. I even drove the wrong way up a one-way street only to be confronted by a van coming the other way and was forced to back up, copping a barrage of abuse from a sweaty, red-faced driver. I even thought of leaving my car in the backstreets of Richmond and running to the MCG, but everything required to do my job was in the car. Excuses started to form in my mind, none of which would stack up. At one time, pointing my car in the direction of my home seemed the only option, abandoning any thought of a career in the game for the solace of my childhood bedroom.

By the time I arrived at the MCG, my Pelaco shirt sweat-soaked to my skin, there was a large throng of players and staff waiting at the changeroom door. The players who arrived early were generally the more committed group who would do extra work even though they had at least three hours of intense and unforgiving work in front of them. Mostly they were the players who knew they had to do this extra work to survive at this level. Time stood still as I fumbled through my big ring of keys to find the one to open the changeroom door.

“Lucky for you Barass hasn’t arrived yet,” said one of the players as he filed past.

I went about my duties, my head swirling with the potential ramifications of my misjudgement. There was a sense of relief when it came time for the players and coaches to leave the rooms, jogging to Flinders Park, and I would soon follow.

As I walked down the railway bridge, I looked towards the witches hat oval I’d constructed what seemed like an eternity ago. From my elevated position, I could immediately see it didn’t look right. The players were doing their pre-training laps on a lopsided, malformed, almost egg-shaped ground, a fact that had not been lost on Ron Barassi and his team of assistants. His pre-training kick-to-kick with Stan Alves was abandoned as all coaches harried around Barass, who had an armful of my misplaced witches hats, and he was attempting to step out the correct configuration of the ground.

Again, my first thought was to find something or someone to blame, make an excuse, but there was nothing. Then I thought about turning around, running in the opposite direction, hiding somewhere, disappearing. But soon, Barass spotted me, put down his witches hats, and faced me, hands on hips, chest out, lip curled. He did not have to say anything. I was being summoned. As I got closer to him, it started. I was now receiving a famous Barassi spray.

It was then that I learned he was also aware that I had turned up late to training.

I remember thinking two things: head up and don’t cry.

I can’t recall exactly what he said; it was all about standards and expectations, professionalism and the impact of my shoddy work. There were, however, five words that have stayed with me.

“Not bloody good enough, Cameron,” he said.

Even my name was said with effect. Barass had a practice of calling people around him some derivation of their name with ‘…aulenko’ added to it. It was a play on the name of one of the game’s greats, Alex Jesaulenko, who he coached to Premierships at Carlton. When I started working at the club, he was soon calling me either ‘Cam-aulenko’ or ‘Schwab-aulenko’. It felt good. I was part of his circle, a sense of belonging, no longer the outsider in an otherwise intimidating environment.

As I turned away, thinking that I had just doused any flickering hope of a career in the game, and from about twenty metres away, still in earshot of the players and staff, I heard him yell:

“Cameron. Don’t do that again.”

As I made my way over to the drinks area where the players and staff congregated, the group was silent as I pretended I had something to do.

As the players fanned out for training, Sam Allica came up to me. Sam was a veteran Demon trainer who, twenty years earlier, ran match-day messages for legendary Melbourne coach, Norm Smith, when Barassi was the champion player and captain. In the few weeks I’d been at the club, Sam had been very kind, always stopping for a chat, sharing stories. He put his strong arm around my waist, pulling me hip-to-hip and walking me away from the group. I looked down at him. He was only a little guy, barely coming up to my shoulder, wisps of silver hair covering his balding pate, his deeply-lined face always ready to break into a toothy smile.

“Did you hear what Barass said?” he asked.

“How could I not?” I replied, unable to stop the tears. “I fucked up, Sam. Fucked up big-time.”

“Sounds like you might have,” Sam responded. “But, did you hear what Barass said?” he repeated.

I turned to face him but kept my head down, ashamed of my tears.

“You could hear him from the fucking MCG, Sam. Everyone heard it. I fucking deserved it,” I snivelled.

“Yes, but did you hear what Barassi said?” he asked again.

I put my head up, meeting Sam’s gaze. He smiled. “He said ‘again’, did you hear that?”

But I couldn’t find the words to answer him.

“What do you think that means?” pressed Sam.

My mind was racing. I couldn’t process. I felt an overwhelming need to lie down on the dusty ground.

“I think I need to sit down,” I say.

We see a park bench under the trees near the bumper-to-bumper Swan Street.

We sit and watch the players finish their pre-training routines with gentle circle work and kick-to-kick, lots of laughing and by-play, as the assistant coaches complete the realignment of my misshapen ground. Barassi blows his whistle, and the players immediately race towards him, last in doing ten push-ups without having to be told.

After a few minutes, Sam asks, “Are you okay, son?”

I look down and realise his hand and forearm are on top of mine. I look down at his arm, lean and sun-blotched with long grey hairs, and I think of Puppy, my grandfather who had died a year earlier.

“I think so,” I respond. “Barass said ‘again’, I get to do it again.”

Sam smiles, eyes glistening. “You get to do it again. Another chance.”

“Let’s go back, eh?” motioning towards the group of support staff preparing drinks to run out to players on this parching day.

“Thanks Sam,” I say. “I will be over in a minute.”

I watched him walk over, smiling at his bandy gait, jockey-like, skinny legs and too-tight white footy shorts.

Sam had been ‘rescuing’ young men like me for the best part of twenty years, and would do so for another couple of decades. Beautiful man.

That night I was back in my childhood bedroom, barely sleeping, catastrophising despite Sam’s reassurances.

I played out a thousand scenarios in my fitful mind. In the middle of the night, I decided that it would be best to resign and join my mates on a beach somewhere for the last few weeks of the summer break.

I got up and wrote a letter to Dick Seddon, the man who had given me this opportunity a few months earlier. It was a letter of resignation, apologising, explaining that I had let him down, as well as Ron, the players and the club, and I felt it was best I quit.

I drove to work with the letter in my coat pocket. I went upstairs to Dick’s CEO’s office, but he wasn’t there, nor was his assistant, Susan, so I left the letter on the keyboard of Susan’s typewriter.

I then went back to my office, past the closed door of the Boardroom where I could hear the voices of Ron, Dick and others in elevated conversation, and convinced that they were talking about me, I decided to take myself out for one last walk around the MCG.

When I returned, I went into my office. On my desk was a large envelope with my name written on it. I opened it with trepidation. Inside was a black and white photo. It was the image that had appeared in The Sun the day before.

Next to the photo was my open Spirax notebook, with a note scribbled.

“If it is to be, it is up to me…Ron Barassi.”

I sit at my desk, looking down at both, when the most recognisable head in football peers around the corner, with a big smile across his broad face.

Ron Barassi.

“I got the blokes from The Sun to get me a copy,” he says, beaming.

He then picks up the photo, studies it, and smiles.

“I’ve still got the taut instep,” admiring his kicking action.

He then holds out his hand, and I think he wants to shake mine. But he puts his open hand softly on my cheek and looks into my wet eyes.

“Are we okay, son?”

I nod. “Yes Barass.”

“We do the common things uncommonly well,” he said.

I’d heard him say this many times in the short time I’d been at the club, somehow thinking it applied only to the players.

“You’re a good lad Cam-aulenko,” he says, “a good lad.”

He left the room. I stared down at my desk, the photo, the already familiar Barassi scrawl in my notebook underneath my handwritten to-do list from the day before, which ominously included, “Set up the training ground,” pre-empting the biggest lesson of my young life.

In the short time I’d been at the club, I had found the experience of being around Barassi to be unrelenting, exhausting, at times mystifying, but also energising. Yes, he was uncompromising. The demands he made of those he needed to match his expectations, to find something, the willpower required to do the common things uncommonly well. But for every withdrawal he made from your energy bank, he also made deposits of love, care and a deep interest in who you are and what you could be. A relationship with Ron was one of constant deposits and withdrawals, hour by hour, day by day, year by year, and this is not for everyone, but at that moment, I realised it was for me.

I was receiving both that trade and education.

“Time to buckle up young fella,” I thought to myself.

Then I remember my letter. I run into Susan’s office and ask her about it, noticing it isn’t on her keyboard.

“Oh, it was from you, was it? I left it on Dick’s desk. He hasn’t seen it yet.”

“Can I get it?” I ask.

“Of course,” she says.

I go into Dick’s office, and in the middle of his leather-topped partner’s desk is my unopened letter.

I grab it, and put it back in my pocket.

“Thanks Susan,” I say as I go past her room.

Play on!

Stay Connected

Please subscribe to our “In the Arena” email.

From time to time to time we will email you with some leadership insights, as well as links to cool stuff that we’ve come across.

We will treat your information with respect and not take this privilege for granted.