Lesson #18 - The strongest steel

I cannot remember when I first heard the quote, “The strongest steel is forged in the hottest furnace”, but I am pretty sure it was the timely reflections of a football coach.

I have also seen the quote given some hyperbole to “The strongest steel is forged by the fires of hell”, and while this is an embellishment for the story I am about to tell, I am also sure the many versions and varieties of ‘hell’ are contextual.

The underlying concept is, of course, that we build strength through adversity, or as Benjamin Franklin observed, “The things which hurt, instruct”.

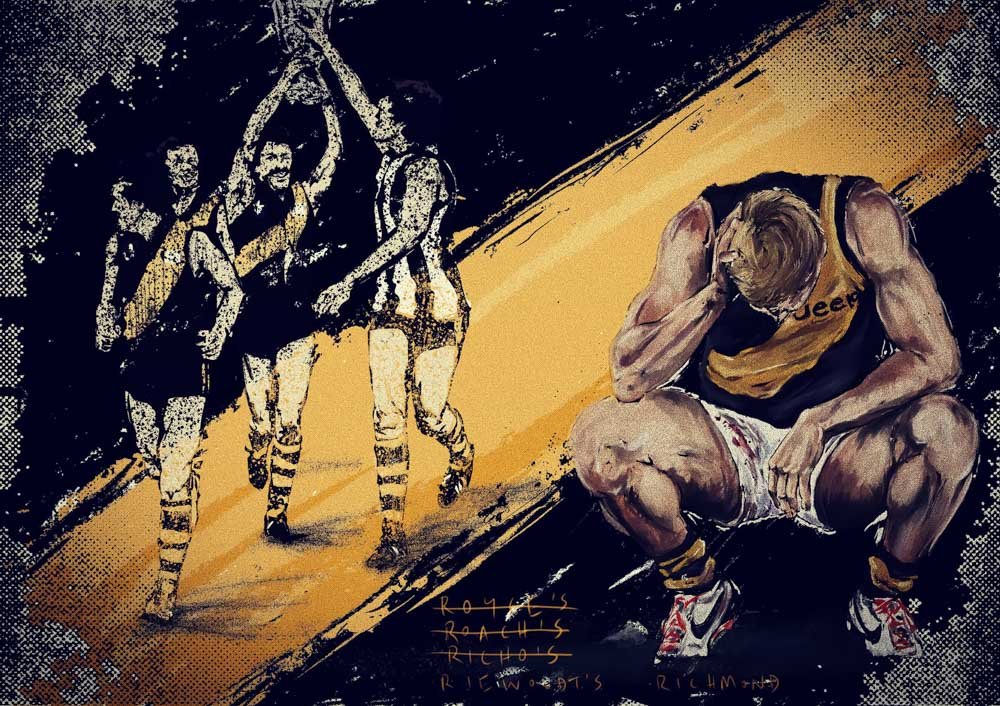

I drew the picture of recently retired Richmond full-forward Jack Riewoldt in 2016 in response to their year of football purgatory.

In the background, I have scrawled the words ROYCE’S, ROACH’S, and RICHO’S’ all crossed out, leaving RIEWOLDT’S RICHMOND. The four famous Richmond names represent a lineage of superstar Tasmanian forwards who metaphorically passed the Tigers’ goalkicking torch for over half a century, kicking more than 2,500 goals between them.

It started way back in the 1960s with Royce Hart, then Michael ‘Disco’ Roach, then Matthew ‘Richo’ Richardson, and finally Jack Riewoldt, as the then bearer of the flame. All are amongst the best to wear the yellow and black, equally proud of their Tassie heritage as they are their Richmond goal-kicking feats.

Each were heroes to their generation. A teenager of today will be trying to reconcile a Richmond team sans Jack Riewoldt, while their parents would likely regale them with stories about the heroics of the inimitable Richo, who shone the brightest light on the darkest period, and reminisce on the day ‘Disco’ Roach announced himself with perhaps the best mark of all time against the Hawks way back in 1979. And then there was Royce, and as my dad once told me, “You only get one of them in a lifetime”.

They represent the timeless nature of barracking for your footy team.

Anointed with a club before you have a first name, identity embedded in a team, not of our choice, for better and for worse. For those who then fall in love with their team on their own terms, as so many do, they bask (or otherwise) in the reflected glory of their club. Everything in life might change, but you would want to have a very good reason to change your footy team.

A footy club demands that you love it. We sing it in our anthems.

“Does your heart beat true for the Red and Blue?”

“Is it good old Collingwood forever?”

“Are you one for all and all for one at Hawthorn?”

“Are you a Navy Blue?”

“And never forget, we’re from Tigerland.”

For those inside the club, with their hands on the levers, this adds layers to an already challenging role, trying to match performance against elevated expectations, ambition with capability, heightened further for those working and playing for one of the ‘big-clubs’.

For those who sign-up for this particular pilgrimage of responsibility, you think you understand what you are getting yourself into but soon realise nothing prepares you for it.

Love is a wonderful emotion, but it is anything but straightforward, particularly when the volume is turned to 10.

I was reminded of this while reading All Black legend Dan Carter’s book ‘The Art of Winning’, where he writes, “Being an All Black brings with it a very specific type of pressure”, and so it is for those representing the hopes of the current generation of ‘big clubs’.

Richmond is one of the ‘big-clubs’ by any definition, but following a period of success from the late 1960s to the early 1980s, which netted five Premierships, an era that all future generations would be compared to, they had done it hard.

But things were looking up. Under coach Damien Hardwick, there had been meaningful progress, with finals three years running. Their forays ended quickly however, bundled out in the first week on each occasion.

“They will learn from this”, the pundits proferred, “they will be better for it.”

But the Tigers buckled badly under the elevated expectations in 2016, winning only eight games and finishing thirteenth. The season started disastrously, losing six of the first seven, but ended even worse, with a 113-point belting courtesy of the Sydney Swans.

It was the kind of loss that elicits more than dismay and disappointment from supporters. Before the game had even ended, you could feel the rage. It became a lightning rod, and for Richmond people, a club that attracts perhaps the deepest form of emotional attachment, there was a sense they had seen this movie before. They were now angry and needed a place to vent, and there was no lack of options. Microwaving your Tiger membership ticket and posting it on social media became a thing, protesting decades of heartache.

No one escaped their wrath, and as is usually the case, most of it focused on the coach despite him leading them into the finals in the previous three years, as well as the senior players, particularly the team leaders, the faces of the club.

But it went even further. The din outside the club started to organise and mobilise, well intended or otherwise, and a Board takeover threatened and soon became a reality.

The player who seemed to epitomise the Tiger journey was Jack Riewoldt, who wore his Tiger heart on his sleeve. My drawing has the ‘ghosts’ of the last Richmond Premiership in the background, something that generations of Richmond players had failed to exorcise, and in 2016, they were back to haunt the current cohort.

But less than a year later, Richmond were Premiers for the first time in 37 years.

During the last quarter of the Grand Final against the Adelaide Crows, the cameras panned the crowd when it became clear Richmond would win. Generations of Tiger supporters were not only hugging, they were crying uncontrollably.

The cameras then point in the direction of the Richmond officials, a proud President Peggy O’Neal quietly smiling, and next to her is Richmond CEO Brendon Gale, and he is crying.

Brendon, or ‘Benny’ as he is known, is also a Tassie Tiger forward, long since retired. He was a talented, dogged and determined competitor as a player in each of his Richmond 244 games during a difficult Richmond era. He and Peggy needed all this ability and resolve when facing the maelstrom of their club under siege.

The football world was demanding change, but it was Benny’s own intuition that drove the need for a thorough review, diagnosing every element of their performance, including his own, and finding that some tinkering was required.

They made several important changes, including appointing the experienced Neil Balme, a former Tiger Premiership hero, into a football leadership role. The most significant decision however, was to ‘stick with their man’, coach Damien Hardwick, who, in a few minutes, would be presented with the Premiership Cup.

The camera then finds the CEO’s old teammate, Matthew Richardson, down at ground level, performing his duties as the broadcaster’s ‘boundary rider’, but he is temporarily unable to, for he is also crying, and so am I as I watch these images on the giant scoreboard from the MCG stands. It was my favourite moment from the Grand Final.

When Jack Riewoldt announced his retirement a few weeks back, he spoke of a catch-up with his skipper and fellow retiree Trent Cotchin after the 2016 season. Believing the narrative that had become the Richmond identity, thinking their opportunity for success had passed them by, they talked about setting the club up for the next generation of Richmond players, using second-year player Daniel Rioli as an example. But less than a year later, they would lead the club to its first Premiership in almost four decades and two more in the next three.

“Whilst we spoke about Daniel playing in the next premiership and being a part of that next Richmond cup, we found ourselves smack bang in the middle of it,” Riewoldt said.

“I think of 2017, and we probably weren’t the most talented list out there, but we had this superpower that we created through an ability to connect on a different level.

“We were an amazing defensive team that year, but we had this trust and belief in each other that we unlocked. Other people saw it as a strength and copied it. Ultimately, we were the only team that could do it in that time, it was unique to us, and I’m really proud of that.”

In my experience, criticism is easy, and finds friends just as easily. Solutions, however, are hard.

The criticisms directed at teams and their leaders when outcomes are less than expected (or hoped), are rarely incorrect. After all, they are there for all to see. But the advice and offerings as to ‘why’ it is happening, and therefore ‘how’ it should be fixed, and ‘what’ decisions need to be made, are mostly less than helpful.

They tend to focus on ‘mechanics’, which is all we get to see from the outside. The noise can also distract from finding the more nuanced and complex solutions the situation demands, which are more likely to be related to team ‘dynamics’ rather than ‘mechanics’.

It is the leaders who create the conditions of performance by embedding a team ethos through a deeper understanding of the respective roles and commitment to carrying them out, week in and week out, and in the moments that matter.

Discussions about culture make for a fascinating and often perplexing conversation. It’s as though people are searching for the secret herbs and spices, a means of short-cutting or ‘hacking’ their way to a high-performance environment.

Strong cultures result from shared struggle and learning, most often over lengthy periods, building cohesion and trust as individuals develop the confidence and capability to ask more challenging questions of themselves and each other, all in the context of the team. They reflect on their failings, try new approaches and experiment. They are prepared to force out incongruent individuals, eventually finding a solution and a way forward tailored to the team.

This is the Richmond story, and their success has become the model for the alternative view of failure. Yes, there will be times when leadership change is needed, but you’d want to be sure. The harder path is to stay the course, and go deeper in order to go forward.

For all the times Brendon Gale stood under the ball and put his body on the line for his club as a player, this was the most courage he showed as a Richmond man, when no one was watching, in his quiet moments, questioning himself while sitting in judgement of others as his CEO role required. And with Peggy O’Neill, he had a President who also asked the hard questions, of him and them, and collectively made some tough decisions, the most significant of which was to stay the path. They set a new standard, not only for themselves but for the competition.

When a team has unexpected success in high-profile sports, it draws a broad range of analysis. People look at the before and after, particularly changes such as new recruits, adjustments to game style, off-field restructuring and the like.

This is the stuff that fills newspaper columns, talkback radio, and the many football panel shows, but this commentary is too obvious and somewhat disrespectful. Yes, changes made post-2016 played a role at Richmond, but at the heart of the club was a group of people with the collective courage and fortitude to work it out for themselves.

Richmond achieved something generations of highly equipped groups of players, coaches, and administrators had failed to accomplish, not because they weren’t good enough, but because it is fucking hard. They failed to find a way in a competition where everyone is trying to find a way, and this is what it takes and why winning at this level is so rewarding.

I have learned that culture isn’t some form of endowment you receive; it is something you have to work for, to learn, and like any skill that is hard to master, it is a process of constant iteration.

In the public domain, culture, as it relates to performance, is usually spoken of in absolutes, most often by people who have never taken responsibility for leadership, or ever been part of, or contributed to a team-based environment.

There was great cohesion in the Richmond group, deep respect for each other, a nuanced understanding of their relative strengths and weaknesses, and they valued their differences. It transcended from President to CEO, to the coach and his players, who played for each other, clearly the aim of any high-performance culture.

I will finish with a quote from football’s Yoda, Neil Balme, on his observations of his club during this time:

“In our game, if you don’t have belief in yourself, if you don’t have a big ego and really high standards, and if you’re not prepared to drive yourself to be the best you can be – you’re no good to us. But if all you are is about you, you’re no fucking good to us. Which is that balance, in the end.

But in football, all you’ve got is people helping each other. There’s nothing else. You know, there are goalposts and a ball and the ground, but nothing else – it’s not a machine you can make better, there’s only your twenty-two on the ground or your thirty staff helping you get to where you want to go.

And the cumulative outcome is amazing when it is cumulative.

Everyone needs a good enough feeling about the overall to be prepared to give everything of themselves, knowing they’re probably not going to make quite as much for themselves, or be quite as good themselves, because you’re giving something to someone else – and that’s not underselling your commitment or your job, but that’s the way it has to be. A sharing of the assets and joys. Let’s make sure everyone’s looked after.

Footy lets us do that because it’s a collective and it’s collaborative, and if you don’t have these, you don’t get the outcome.”

Play on!

Stay Connected

Please subscribe to our “In the Arena” email.

From time to time to time we will email you with some leadership insights, as well as links to cool stuff that we’ve come across.

We will treat your information with respect and not take this privilege for granted.